“Pou eime?”

“Ti?”

“Pou eime?”

I hesitated to give any response to the question for a few seconds, but I finally answered.

“Spiti?”

My answer was in itself a question.

After living in this house for six years why is my father asking me where we are? We are sitting on the badly torn leather couches that are covered in this horrible grey colour that he bought, aren’t we?

The moment bombarded my six year old brain all day. I sat there in the middle of our three seated couch, legs crossed like I always had them, as my little self wondered what just happened.

Are the white walls with all our photos hanging by nails not familiar? Are the 90’s style skirting’s and light features not a common sight for him? Is that wooden table only centimeters away from him, and the first place he sits at every night after work, not memorable? And more importantly, is his only daughter not recognisable at this very moment?

I mean, he spoke to me like he knew who I was, so I guess I had nothing to worry about. I wasn’t losing my mind, nor my father, or was I?

I was too young for that. My lack of maturity and experience in life did not prepare me for what was happening in the months to come.

We’re in March now, and days after that incident which still lingered in my mind, it was my seventh birthday.

My mum organised a little party in the garage. Friends from school came, all my cousins, aunties and uncles and even relatives that I wouldn’t be able to name, and never see now, joined the rest of us.

I always call myself a bit of an accident for my mum and dad. I wasn’t supposed to happen; I just did, and I was the biggest and greatest surprise for my parents who were in their 40s when I was born. And the fact that I was a girl after they had had already two boys made me somewhat special.

My birthday was the day everyone reflected and remembered just that.

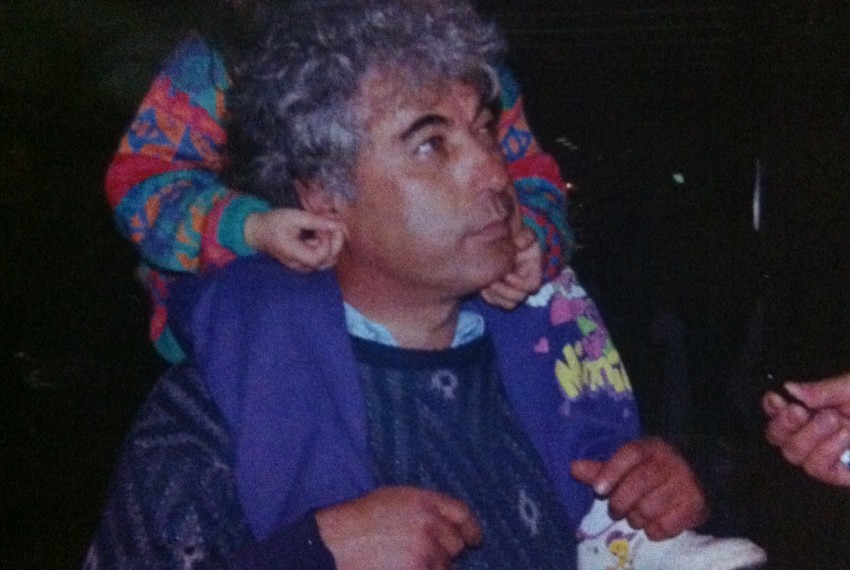

However, my seventh birthday was different. It wasn’t my day, but more about how Dad was going. The attention was on him the whole day. I even remember him sitting down with his great old belly near the brick wall, rotating his grey haired head, staring into the scenery like a lost child looking for his puppy. My dad didn’t lose a puppy though, it seemed as though he lost himself. I don’t even remember him being near me for the cutting of my cake. He was on his own in his own little world. Everyone knew why, while I was left in the dark.

Days after it became obvious to me that Dad was not doing so well.

There were so many trips to this doctor; we had to go see that doctor.

I even recall my family, which consisted of my two brothers, the eldest Theo and then Paul, my mum and Paul’s girlfriend at the time, standing around my dad while he was laying upright in a bed being examined by doctors. The doctor was talking to the adults about the situation. I wasn’t really listening. It was all jargon to me, so I zoned out. But for a moment I must have switched on again. I remembered the incident at home when Dad wanted to know where we were. I quietly let Paul’s girlfriend know about that moment while she was comforting me by laying her hands on my shoulders.

She spoke out and alerted them, “Georgia just let me know that the other day he asked her where they were and they were at home!”

A lot of umming and arghing happened after she mentioned my episode with him. That moment at home was possibly the last time I had any verbal exchange with my dad.

That all went on for about a month until the hospital of St Vincent became my second home.

I didn’t even go home after school anymore. Someone would pick me up and we would go straight to the hospital. There wasn’t even time for dinner. Most the time I had my favourite little Happy Meal from McDonald’s and I’d take it up to the room with me.

I knew we were there for Dad but I didn’t really speak to him at all.

He was losing so much weight. The breathing mask became his new daily accessory; a bit different from his usual taxi driver’s uniform. He had to get used to the fact that the hospital bed would be his new place of resting for a while and not his little home in north of Melbourne.

As it became a daily routine, I got to my dad’s room again with school bag and uniform on tow. He dominated his usual spot on the bed and I was about to say hello, dropping my bag on the floor when all of a sudden, through the breathing mask he muffled, “Georgia!”

Out of sheer excitement my mum began to cry.

“Oh My God, he remembered your name,” a third person in the room said. Too be completely honest I didn’t know he forgot it.

So, it came together. Dad lost all his memory and somehow it was all coming back to him.

If he was getting better, then why a week or so later did I follow the same routine, but this time found myself heading to a different room and was confronted by disgusting stitches stretching from one side of my dad’s forehead to the other?

Nothing, but nothing made sense!

The routine didn’t change in May but the hospital did. At night, I was staying at three of my aunties homes on three different occasions. Mum was too busy at the hospital to take care of me I guess, so I had to stay with a different sister of hers at a time. I stayed with thia Agnoula, thia Georgoula and thia Lelia. I don’t know where my brothers were staying though. Maybe at home, but nonetheless, it was a fun sleep over for the little oblivious me.

My last visit to that hospital had me sitting on Theo’s lap as he cried. I watched him cry while we sat near the bed my dad was on, still sporting that breathing mask.

He must have noticed I was watching him, because he looked up at me and said, “Nah, I’m not crying. I’m just sad ‘cause Dad’s going to go up there” and he pointed up to the ceiling. I knew exactly what he meant, but at the same time it was too confusing for me to comprehend.

The last aunty I stayed with was thia Agnoula. She had set up a bed for me on the floor of her room near hers and thio Liaso’s bed.

It must have been late in the evening of the 12th of May when the phone rang and thia Agnoula answered it in a hurry. Don’t know who was on the other side, but her words to that person were, “Pethane?”

In translation for those who don’t know, “Did he die?”

Again, I was left in the dark. Why would dad be dead?

Whatever happened after that, I don’t remember. But I do recall spending time facing an audience at the front of the Fawkner Greek Orthodox church next to a casket while everyone wore black, sobbed and came to wish us, whatever you wish when someone so dear passes away. I think I was the only one that wasn’t crying in church which was way over crowded. I even wondered what my primary school teachers were doing there.

And I don’t forget Mum going with the option of having Dad at home for a few hours, while everyone said their last goodbyes.

It was an open casket, in the middle of the dinning room, which usually is vibrant and bright with pink and white furniture. But that day it was filled with black and my father’s body in a suit as he lay in his new bed. I kissed my finger tips and laid them on his forehead and my only reaction was towards the cold temperature of it. I also noticed how hard it felt and how pale he looked. It’s like I really didn’t believe he was gone. I didn’t believe that this was a time to be sad and I refused to let it sink in, thinking he was going to come back and that’s how he looked and felt just for now.

Until this day I don’t understand fully what happened. And no one in my family will ever speak to me about it to make me aware. At the same time I’m not willing to ask any questions in fear of what I might find out. I’m still in the dark. But no one will ever realise what an impact not having a father had on me and my family. It almost tore us apart when it should have brought us closer together. But that’s a story for another day.

2014 and now I cry. I didn’t know then, I didn’t get why, but now I do and now it hurts.